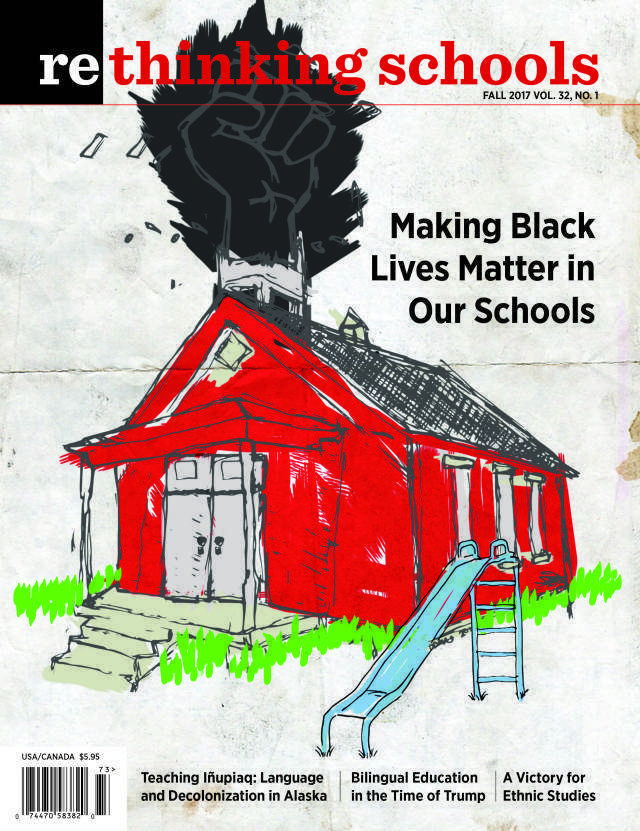

By Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian

On Monday April 1, 1967 “George Dowell and several neighbors from North Richmond, California . . . heard 10 gunshots. Sometime after 5:00 a.m., George came upon his older brother Denzil Dowell lying in the street, shot in the back and head. Police from the county sheriff’s department were there, but no ambulance had been called. . . . [The] sheriff’s office reported that deputy sheriffs Mel Brunkhorst and Kenneth Gibson had arrived at the scene at 4:50 a.m. on a tip from an unidentified caller about a burglary in progress. They claimed that when they arrived, Denzil Dowell and another man ran from the back of a liquor store and refused to stop when ordered to halt. Brunkhorst fired one blast from a shotgun, striking Dowell and killing him. . . .

For the Dowells, the official explanation did not add up, and community members helped the family investigate. . . . There was no sign of entry, forced or otherwise, at Bill’s Liquors, the store that Dowell had allegedly been robbing. Further, the police had reported that Dowell had not only run but also jumped two fences to get away before being shot down. But Dowell had a bad hip, a limp, and the family claimed that he could not run, let alone jump fences. . . . A doctor who worked on the case told the family that judging from the way the bullets had entered Dowell’s body, Dowell had been shot with his hands raised. . . . Mrs. Dowell publicly announced, ‘I believe the police murdered my son.’ . . . A white jury took little time deciding that the killing of unarmed Dowell was ‘justifiable homicide’ because the police officers on the scene had suspected that he was in the act of committing a felony. Outraged, the Black community demanded justice.”

—Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr. Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party

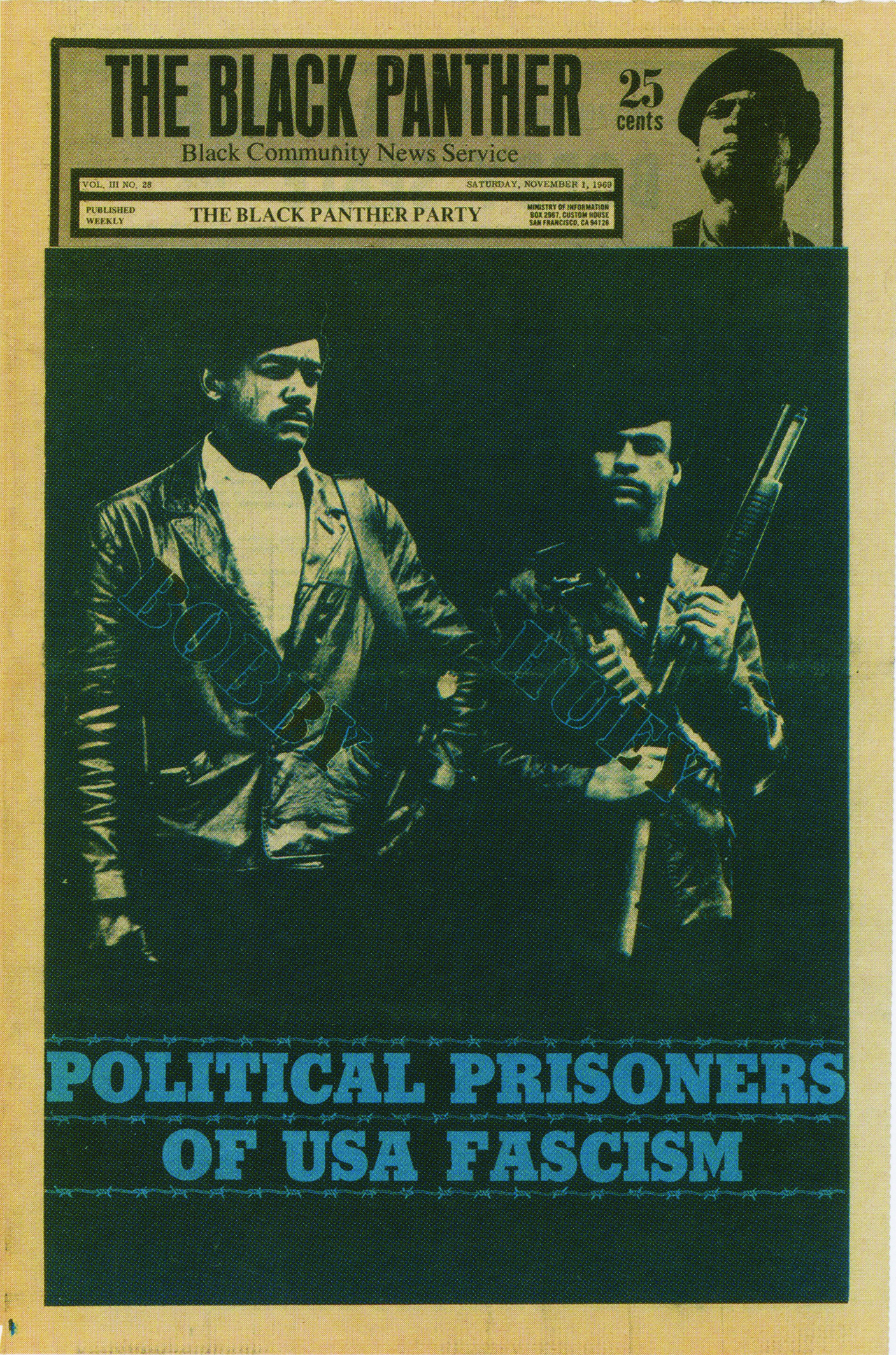

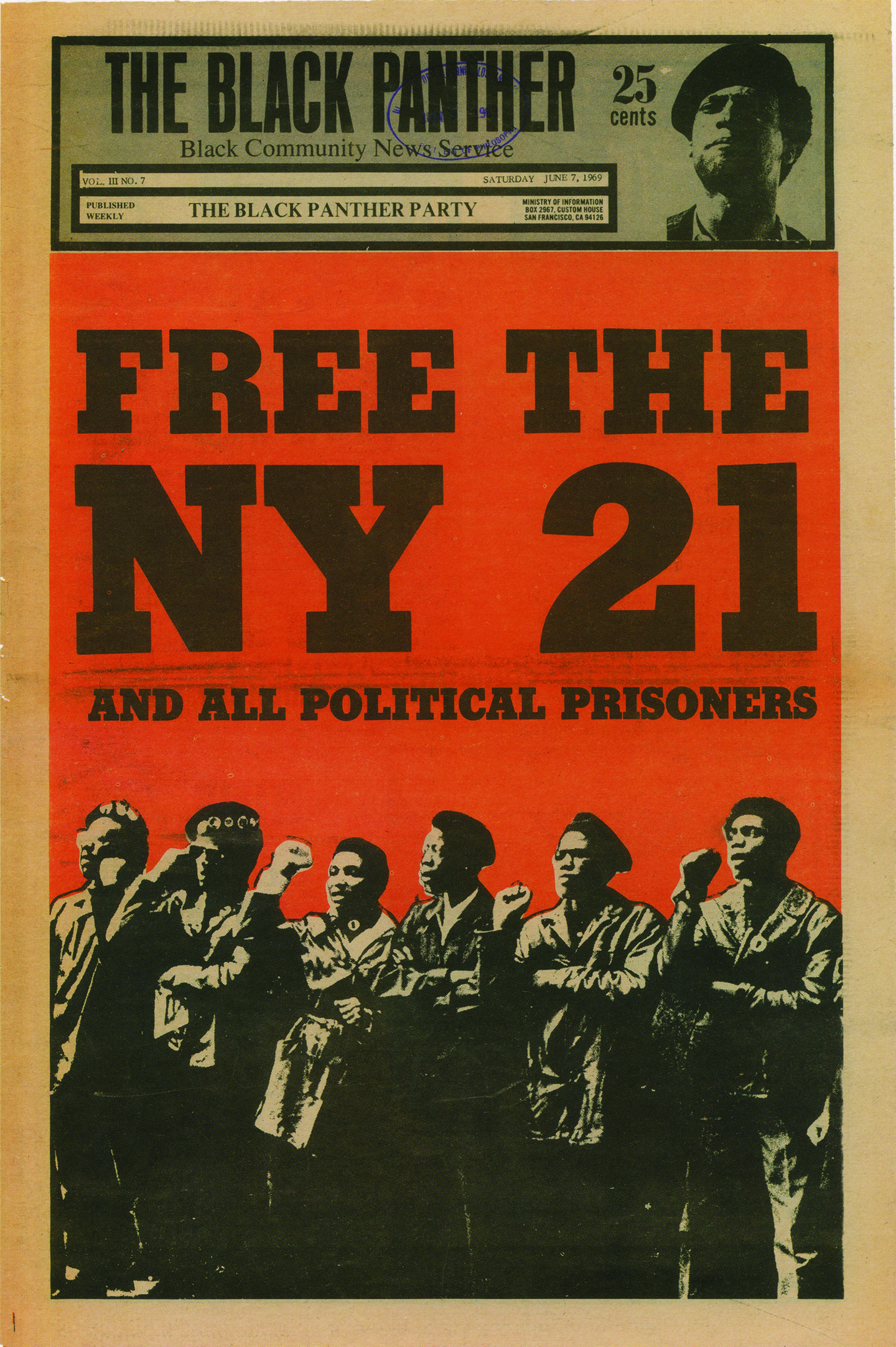

Helping North Richmond’s Black community demand justice for the killing of Denzil Dowell was one of the first major organizing campaigns of the Black Panther Party, and the first issue of The Black Panther newspaper, which at its height around 1970 had a circulation of 140,000 copies per week, asked, “WHY WAS DENZIL DOWELL KILLED?” Anyone reading the story of Dowell today can’t help but draw parallels to the unarmed Black men and women regularly murdered by police. The disparity between the police’s story and the victim’s family’s, the police harassment Dowell endured before his murder, the jury letting Dowell’s killer off without punishment, even the reports that Dowell had his hands raised while he was gunned down, eerily echo the police killings today that have led to the explosion of the movement for Black lives.

Yet when we learn about the early years of the Panthers, the organizing they did in Richmond — conducting their own investigation into Dowell’s death, confronting police who harassed Dowell’s family, helping mothers in the community organize against abuse at the local school, organizing armed street rallies in which hundreds filled out applications to join the Party — is almost always absent. Born just over 50 years ago, the history of the Black Panther Party holds vital lessons for today’s movement to confront racism and police violence — yet textbooks either misrepresent or minimize the significance of the Panthers. Armed with a revolutionary socialist ideology, they fought in Black communities across the nation for giving the poor access to decent housing, health care, education, and much more. And as the Panthers grew, so did the issues they organized around.

This local organizing that the Panthers engaged in has been largely erased, yet it is precisely what won them such widespread support. By 1970, a Market Dynamics/ABC poll found that Black people judged the Panthers to be the organization “most likely” to increase the effectiveness of the Black liberation struggle, and two-thirds showed admiration for the party. Coming in the midst of an all-out assault on the Panthers from the white press and law enforcement — including FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s claim that the Panthers were “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country” — this support was remarkable.

The Textbook Version of the BPP

A few of the major textbooks don’t even mention the Black Panthers, while most spend only a sentence or two on the organization. Even the small number that do devote a few paragraphs to the Party give little context for their actions and greatly distort their ideology.

Textbooks often associate the Panthers with violence and racial separatism. For example, according to Teachers’ Curriculum Institute’s History Alive! The United States Through Modern Times, “Black Power groups formed that embraced militant strategies and the use of violence. Organizations such as the Black Panthers rejected all things white and talked of building a separate black nation.” While ignoring that the Panthers believed in using violence only in self-defense, this passage also attempts to divide the Panthers from “nonviolent” civil rights groups. The Panthers didn’t develop out of thin air but evolved from their relationships with other civil rights organizations, especially the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The name and symbol of the Panthers were adopted from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), an independent political organization SNCC helped organize in Alabama, which was also called the “Black Panther Party.” Furthermore, SNCC allied with the Panthers in 1968 and although the alliance lasted only five months, it was a crucial time for the growth of the Panthers.

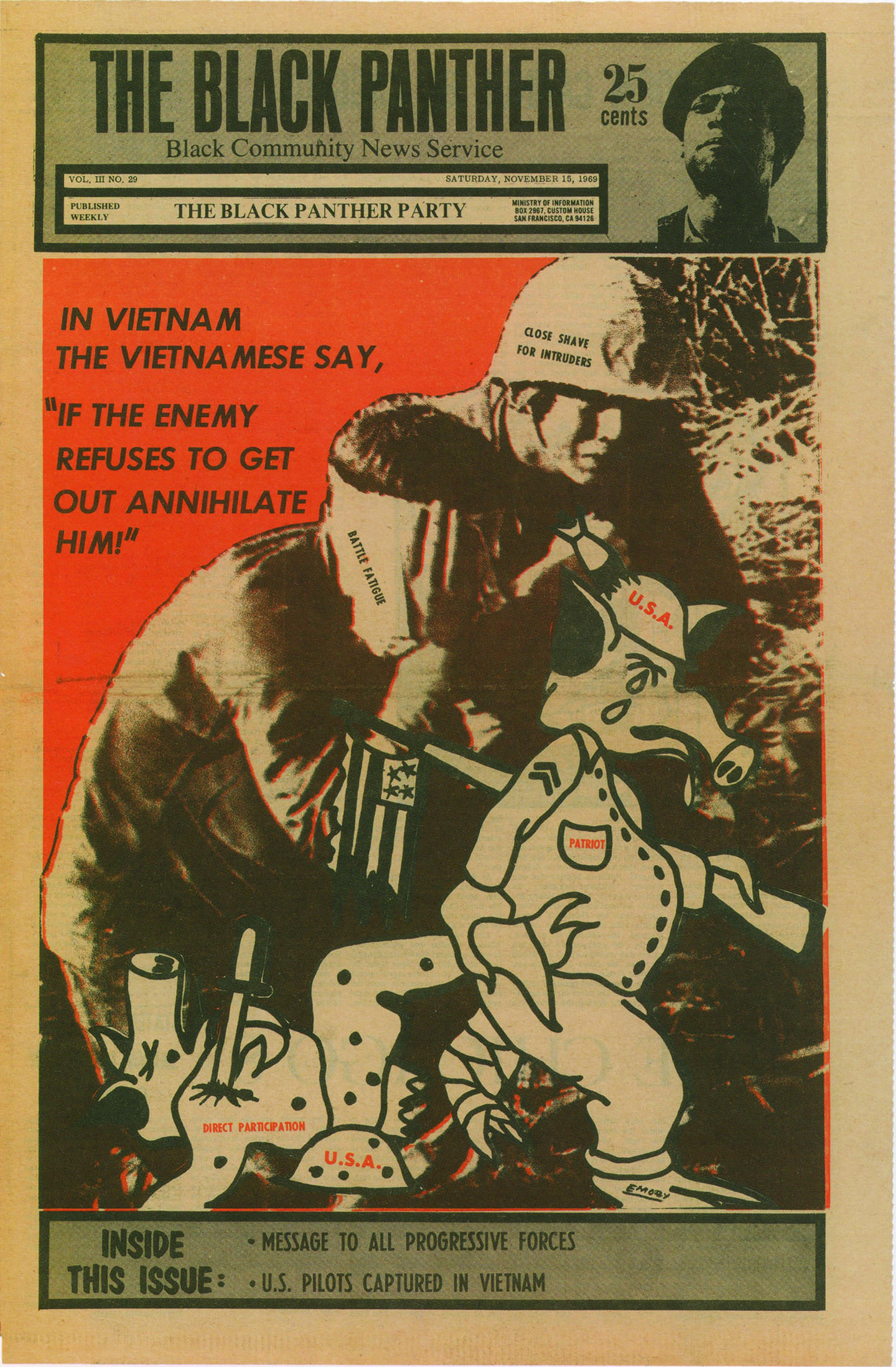

The passage from History Alive! also incorrectly paints the Panthers as anti-white, erasing their important work building multiracial coalitions. Most famously, Chicago Panther leader Fred Hampton organized the Rainbow Coalition that included the Puerto Rican Young Lords and the Young Patriots — a group of poor, Southern, white migrants. The Black Panthers helped the Patriots set up their own community service programs. In California, the Panthers made an important alliance with the mostly white Peace and Freedom Party, which in 1968 ran Eldridge Cleaver for President in an attempt to provide an antiwar, anti-racist alternative to the Democratic Party. An editorial in The Black Panther explained: “The increasing isolation of the black radical movement from the white radical movement was a dangerous thing, playing into the power structure’s game of divide and conquer.”

Other textbooks also erase the socialist character of the Black Panther Party. Holt McDougal’s The Americans reads, “Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded a political party known as the Black Panthers to fight police brutality in the ghetto.” While the textbook later acknowledges other things the Panthers advocated, by reducing the reason for their founding to fighting police brutality, The Americans profoundly diminishes the important ideological basis of the party. More clearly than any other national civil rights organization, the Panthers linked the fight against racism with the fight against capitalism. As Panther Huey Newton explained, “We realize that this country became very rich upon slavery and that slavery is capitalism in the extreme. We have two evils to fight, capitalism and racism. We must destroy both.” The Panthers understood that Black people could not achieve socialism on their own and their work building multiracial anti-capitalist coalitions flowed from that analysis. In fact, the Panthers developed an education requirement for joining the party that consisted of reading 10 books relating to Black liberation and socialism.

Several textbooks also blame the Panthers for the end of the Civil Rights Movement, while simultaneously ignoring or downplaying the role the FBI played in destroying the party. In a later section in The Americans, the authors write, “Public support for the Civil Rights Movement declined because some whites were frightened by the urban riots and the Black Panthers.” What textbooks like this fail to mention is the decline in public support was a result of the counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) of the FBI. According to scholar Ward Churchill:

The Black Panther Party was savaged by a campaign of political repression, which in terms of its sheer viciousness has few parallels in American history. Coordinated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation . . . and enlisting dozens of local police departments around the country, the assault left at least 30 Panthers dead, scores of others imprisoned after dubious convictions, and hundreds more suffering permanent physical or psychological damage. Simultaneously, the party was infiltrated at every level by agents provocateurs, all of them harnessed to the task of disrupting its internal functioning. Completing the package was a torrent of “disinformation” planted in the media to discredit the Panthers before the public, both personally and organizationally, thus isolating them from potential support.

With minimal and problematic coverage in the history textbooks, there is little curriculum for teachers hoping to provide students with the crucial history of the Black Panther Party. This is why we were excited last year to hear that PBS began distributing Stanley Nelson’s new documentary Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution . The documentary is an essential tool for the classroom and gives high school teachers an incomparable visual companion to teaching the Panthers. Like any documentary, the film has some oversights that teachers should be aware of. Although it discusses the Panthers’ 10-Point Platform, it doesn’t do a great job of explaining the Panthers’ Marxist ideology. It also doesn’t provide enough historical context for the Panthers’ activities, making it difficult for students to fully understand both the rise and fall of the Party. And in its attempt to tell the national story of the Panthers, it sometimes skips over important local organizing efforts. But chunked into sections and coupled with readings that help flesh out the documentary’s omissions, it is a crucial addition to any social justice teacher’s tool chest.

Teaching the Panthers Through Role Play

To introduce the film and to try to give students a fuller picture of the party’s history, we developed a mixer activity in which each student takes on a role of someone who was in, or connected to, the Black Panthers. Students are given a role with a thumbnail sketch of that person’s biography along with details that help illuminate aspects of the party. In all of the roles, we tried to emphasize why people joined the Black Panther Party. For example, the role of Kathleen Cleaver begins:

As a young Black woman growing up in Alabama in the 1950s, you wanted to challenge injustice. You were inspired by powerful women leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). . . . These women were creating a social revolution in the Deep South and all worked with SNCC. . . . In 1966, you went to organize in SNCC’s New York office and then to Atlanta, Georgia. You had joined SNCC at the time it took up the slogan “Black Power,” and you saw the Black Panther Party as taking the positions SNCC was headed toward. . . . You decided to move to San Francisco and join the Panthers.

Among the other roles is Ruby Dowell, Denzil Dowell’s sister who joined the party after the organizing the Panthers did in Richmond.

We also tried to highlight the repression the Panthers faced along with some of the lesser known but important stories of Panther community organizing. The role for Lumumba Shakur, founder of the New York Black Panther Party chapter, explains how the entire New York Panther leadership was arrested on flimsy evidence. Part of the role’s description:

You spent two years in prison while the trial proceeded. You organized prisoners to fight for better living conditions and at one point took control of the jail from the prison guards. You demanded and received bail hearings for every prisoner. Hundreds of prisoners were released as a result of the new hearings.

Students also encounter Panther allies like William “Preacherman” Fesperman of the Young Patriots, Madonna Thunder Hawk of the American Indian Movement, Gloria Arellanes of the Brown Berets, and Jose “Cha-Cha” Jimenez of the Young Lords. They also meet Panther “enemies” like FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Los Angeles Police Officer Pat McKinley.

One of the most overlooked aspects of the Panthers we tried to highlight was their role in the struggle for anti-racist education. Historian Donna Murch details how the Panthers had their origins in “agitation for Black Studies courses and debates about the ‘relevance’ of education,” and describes the membership of Panthers as “composed largely of Southern migrants under 25, including many students recruited from local high schools and community colleges…” The Panthers were originally formed out of a study group at Oakland’s Merritt community college. The Panthers’ belief in the need for an education beyond what was being taught in the school system led them to develop a network of liberation schools for youth.

In the mixer, the role of Ericka Huggins highlights the Panthers’ flagship liberation school in Oakland. Other roles highlight the Panthers’ fight for ethnic studies and their free breakfast program that fed hundreds of hungry children before school and was eventually adopted by the U.S. education system — one of the party’s most meaningful and lasting reforms.

Lastly, we tried to include criticisms of the Panthers in the roles — not just from the police and conservative politicians, but from Black Panthers themselves. Often students can glorify the Black Panther Party, especially students of color who are regularly harassed by police and are justifiably impressed with the Panthers’ bold defiance against what they called “the pig power structure.” But the Black Panther Party existed as a national organization for only a short period, and while a large responsibility for their destruction should be put on the FBI and police efforts to destroy the party, it’s also important for students to ask whether the Panthers could have done anything differently. Whether it is the sexism some female Panthers experienced, or the ideological debate that caused an eventual split in the party, we wanted to provide students with tools to critically assess this complex history.

To start the activity, we distribute roles to students and ask them to read them several times, underline important information, and list out three or four crucial facts on the back of the role. Students are often blown away by the stories presented. “My character’s a badass!” one student exclaimed after reading about Bobby Seale’s acts of defiance in the courtroom when he was put on trial after participating in the 1968 antiwar demonstration at the Democratic National Convention.

When students finish reading, we give out eight questions that guide them as they circulate around the room, meeting others and finding a different person to answer each of the questions. For example, “Find someone who has an opinion on the role of women in the Black Panther Party. Who is this person and what is their opinion?” We encourage students to take their time — the point of the mixer is not to race through and get all the answers to the questions, but to learn from the various stories in the room to get a fuller picture of the Black Panther Party. As teachers, we participate in the mixer as well. It’s helpful to take a role with a more complex critique that might be hard for students to explain, like Stokely Carmichael or Luke Tripp of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. Students are often eager to learn the stories in the room and a buzz fills the air as they grab one another and share their roles.

At the end of class — with at least 20 minutes left, we ask students to head back to their seats and silently write on four questions:

- What were some of the things you learned about the Black Panthers that you didn’t know before the mixer?

- Whose story did you find most interesting or surprising?

- What did you think of the critiques of the Black Panthers you encountered?

- What would you like to know more about?

We’ve always been impressed by the rich discussion these four questions produce. Students are often surprised to learn the story of Richard Aoki. “I thought they’d only allow Black people into their group, but Aoki was Japanese American,” Maya wrote. For many students this is the first time they learn about Latinx or Asian American radicals. Aliyah exclaimed, “It was cool to learn about Gloria [Arellanes] and Cha-Cha Jimenez. I didn’t know that Mexicans and Puerto Ricans were fighting in the same ways as the Panthers.” “Yeah, my mom told me about the Brown Berets,” Ayanna stated, “but I didn’t know that they were connected to the Panthers.”

Students are often shocked at the level of violence the Panthers faced at the hands of the FBI. “It was sad to hear the story of Lil’ Bobby Hutton,” Brandon wrote. “He was trying to help his people and was shot more than 12 times with his hands up. He was only 16!” David added, “I found it interesting the way the FBI set up the BPP. It’s clear the government did not want them to succeed.” More specifically, James noticed, “The FBI sent fake letters to the Oakland and New York Panthers to create tensions between them. I didn’t realize the FBI was so involved in breaking them up.”

We’ve found that students can often be impressively articulate when evaluating the critiques they come in contact with during the mixer. Keisha wrote, “I thought Luke Tripp’s ideas made sense when thinking about how to fight capitalism. He founded the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement in Detroit and was focused on helping working-class Blacks. He thought the confrontations with police would just get Panthers thrown in jail and that they should focus on organizing strikes.” Melanie disagreed, “I actually think the confrontations with police were important because it showed people the Panthers weren’t scared.” Madison grappled with the differing views of sexism in the party that she encountered: “It was interesting that Roberta Alexander called out sexism in the BPP and thought they didn’t give women equal rights. Other Panther women I met disagreed. People still have sexist attitudes toward women and women don’t have equal rights so that was interesting to think about.” Other students defended the Panthers against critiques from the right and left. “[California State Assemblyman] Donald Mulford said that he wanted to protect society from Black people with guns. But I feel like society needs to be protected from white people with guns,” declared JT. “I really like Stokely Carmichael,” Gregory began, “but I disagree with his critique of the Panthers for making alliances with white people. I get where he’s coming from, but you can’t fight racism with racism.” Without realizing it, Gregory’s words echoed Chicago Black Panther leader Fred Hampton’s.

We hope the mixer we wrote, Stanley Nelson’s new documentary, Wayne Au’s lesson on the Panthers’ 10-Point Program, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca’s lesson on COINTELPRO, can be starting points for educators who hope to arm a new generation with the story of the Panthers. As the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party passes by, these lessons should be just a few of many to come that help teachers and students explore this rich — and too often ignored — history.

Resource: Click here for the Black Panther Party mixer.

Adam Sanchez (adam@rethinkingschools.org) is an editor of Rethinking Schools magazine. Sanchez teaches at Harvest Collegiate High School in New York City and works as curriculum writer and organizer with the Zinn Education Project.

Jesse Hagopian (jesse@rethinkingschools.org) is an editor of Rethinking Schools magazine, teaches at Garfield High School in Seattle, and is editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing (Haymarket).